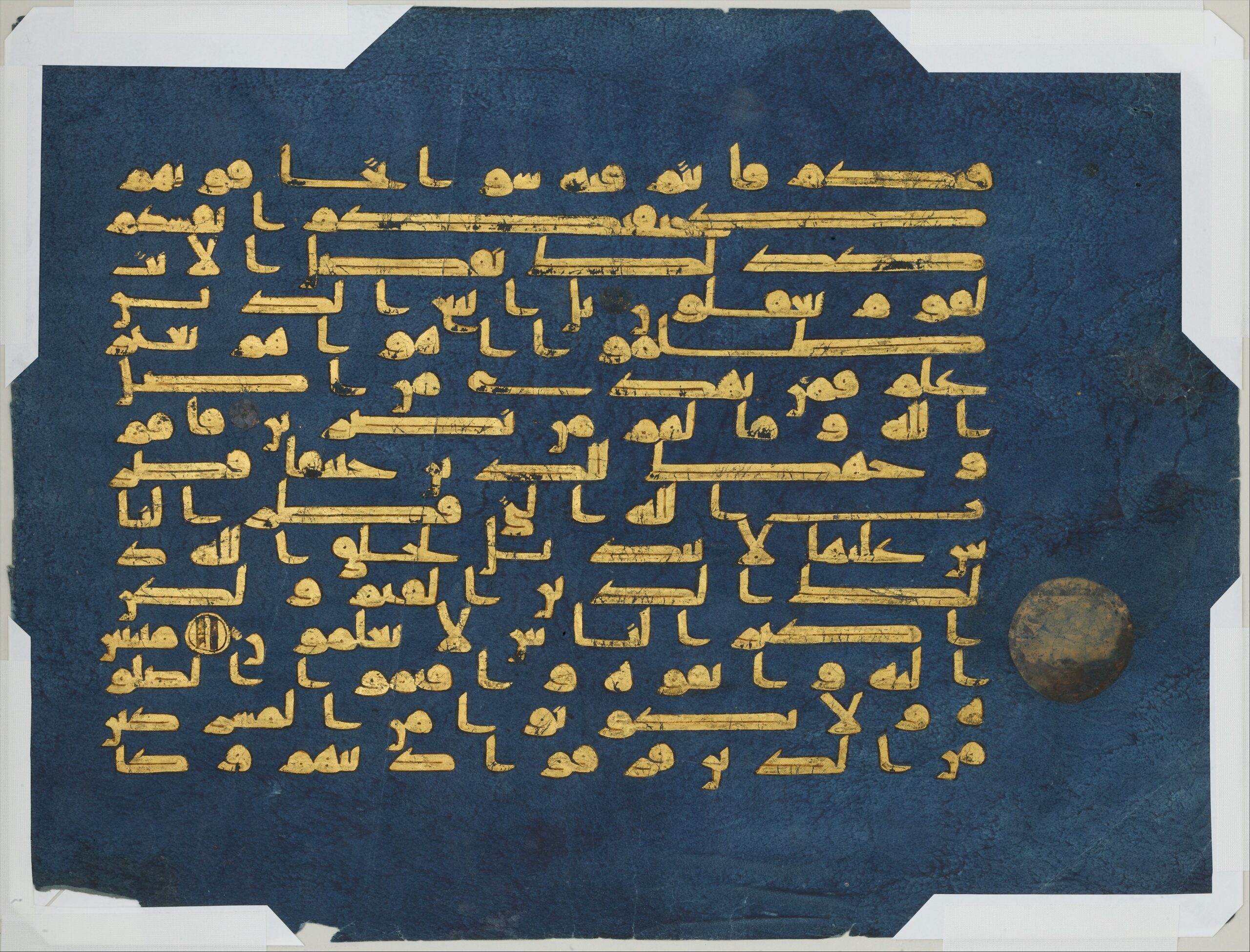

The "Blue Qur'an"

The “Blue Quran” is one of the most famous and visually stunning manuscripts of the Islamic world.

Produced in the 9th to 10th centuries during the rule of the Fatimid or Umayyad dynasty, this luxurious manuscript is renowned for its striking visual appearance.

Here are some key features and historical details about the Blue Quran:

Material and Aesthetics.

What makes the Blue Quran distinctive is the use of rich indigo-dyed parchment on which the text of the Qur’an is inscribed in gold. This contrast between the deep blue background and the gold script is visually captivating, setting it apart from other Islamic manuscripts. Silver in the Blue Quran was utilized to mark verse divisions.

Parchment is a material made from the skin of animals, typically sheep, goats, or calves, which was prepared for writing or printing. This material was commonly used before the widespread adoption of paper. Ancient and medieval manuscripts, scrolls, and some early books were often written on parchment.

Indigo is a deep blue dye that is derived from the leaves of certain plants. It has been used for thousands of years across various cultures to dye textiles and other materials.

Gold and silver is applied using these steps.

Leaf Production.

Both gold and silver can be processed into extremely thin sheets called “leaves.” This involves melting down the raw metal, casting it into thin ribbons, and then repeatedly hammering it until it’s exceedingly thin. The resulting sheets are delicate and can easily tear.

Application.

Once the writing surface like parchment is prepared with a binding medium or mordant to make it slightly sticky in the shape of the desired letters or designs, the fragile gold or silver leaf is carefully lifted (often with special tools or brushes) and placed onto these prepared areas.

Pressing Down.

After placing the leaf onto the sticky areas, it is gently pressed down to ensure it adheres to the mordant beneath. Burnishing, or polishing with a smooth tool or stone, often follows this step, both to enhance the metal’s shine and to further secure its bond to the parchment.

Primary Distinguishing Feature.

In the Blue Quran, the primary distinguishing feature is the gold Kufic script on blue indigo-dyed parchment.

Silver in the Blue Quran was utilized to mark verse divisions. These silver roundels serve as visual indicators separating individual verses, providing clarity and aiding in the reading of the text. The combination of the gold script for the main text and the silver markers for verse divisions creates a striking visual contrast and adds to the luxury and uniqueness of the manuscript.

However, as is common with silver in ancient manuscripts, over time, the silver has tarnished in many places, turning black or dark. This can change the visual appearance of these markers, but they originally would have shone brightly against the blue background.

Script.

The script used in the Blue Quran is an early form of the North African Kufic, a highly angular and geometric style of Arabic calligraphy. The elegant, almost minimalist, nature of this script complements the simplicity of the blue and gold color scheme.

Origins.

The exact origins of the Blue Quran are debated among scholars. It’s thought to have been produced either in North Africa, under the Fatimids, or in Spain, under the Umayyads. Its luxurious design suggests it was likely commissioned for a ruler or a significant institution. The Fatimid origin is one of the prominent theories regarding the creation of the Blue Quran. However, it’s not the only one, and as of now, there isn’t unanimous consensus on its exact provenance.

Significance.

Beyond its aesthetic value, the Blue Qur’an is a testament to the grandeur and sophistication of the Islamic world during the early centuries of its existence. The lavish use of gold and the high quality of the parchment and dye indicate the considerable resources and skills employed in its creation.

Current State.

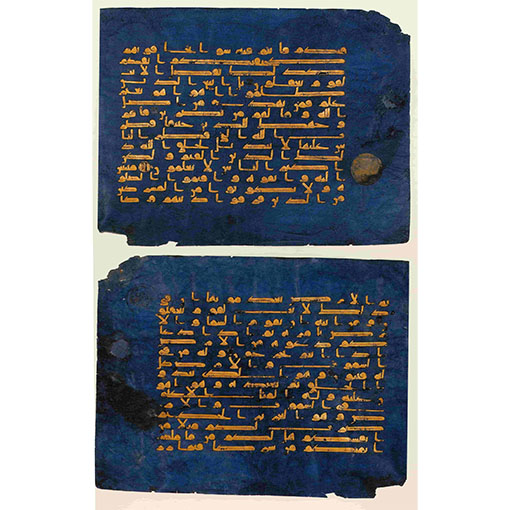

The Blue Qur’an is not a single bound volume but exists in sections scattered in various museums and private collections around the world. Some significant portions can be found in institutions such as the National Institute of Art and Archaeology in Tunis, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto also has a couple of folios in its collection. If you intend to visit these museums specifically to see the Blue Quran, we recommend contacting the museums in advance to confirm its current exhibition status.

Conservation.

The Blue Quran’s remarkable condition today is due in part to the high-quality materials used in its production, but also to the efforts of conservators and curators who have worked to preserve it for future generations.

The Blue Quran serves not only as a religious text but also as a significant artifact from the history of Islamic art and a testament to the high level of craftsmanship and aesthetic sensitivity of the period in which it was created.

Criticism.

From a religious perspective, Islam emphasizes humility, modesty, and warns against excessive pride or ostentation. Given this, one might argue that such a luxurious presentation could be seen as overly ostentatious. However, it’s crucial to understand these artifacts in their historical and cultural context. The patrons and creators of such manuscripts likely viewed their efforts as a way of honoring the divine word rather than merely showing off wealth.

Also, the Blue Qur’an is written on parchment, which is prepared from the skin of animals, often calves, sheep, or goats. Given the size of the Blue Qur’an, it is evident that the production of this magnificent manuscript required a significant amount of parchment.

Estimates regarding the exact number of sheep needed to produce the Blue Quran vary, but some sources suggest that it could be in the hundreds. Each page of the manuscript would have required at least half a skin, and considering that the Blue Quran is believed to have originally contained hundreds of folios, it’s plausible that between 500 to 1,000 sheep were used.

However, it’s essential to consider the context: during the medieval period, livestock was regularly raised and slaughtered for food, and their hides were routinely used for various purposes, including the production of parchment for manuscripts. The production of the Blue Quran would have been a monumental effort in many respects, and the use of parchment from hundreds of sheep further underscores the significant resources invested in its creation.

Image Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York